Sinkyone Wilderness State Park, Usal Beach, California

August 3 to 6, 2014

"In the early days, Georgia-Pacific had allowed basically unrestricted free camping there for many, many years. It was not party central or the Wild Wild West. It was more like a family campground and a backpacking trail head. When it was added to the California Park System in 1986, it was what we call a 'free-for-all'. The rangers would catch up with those people sooner or later and give them a ticket. You can't have people target shooting in campsite one and a family with little kids running in campsite two. The two things do not mix."

John Jennings, a retired ranger, the first person to ever patrol at Usal Beach in 1986

Hike Information

The Lost Coast is an isolated undeveloped and fairly isolated area of the California North Coast in Humboldt and Mendocino Counties. It acquired its name during the Depression when local inhabitants moved to find jobs. Because the local geology makes it difficult for road builders to establish roads, the villages within the Lost Coast are only accessible by land via small mountain roads.

Jim and Brian arrived at Bob's house in the General II (black instead of last years white). After getting supplies and packing the car, we left for Ft. Bragg. We had lunch at Bear Republic Brewing Company in Healdsburg and sampled a few beers. We continued north on Highways 101 and 1 and reached Ft Bragg that afternoon. We stayed that night at the Best Western Vista Manor Lodge and dined at the North Coast Brewing Company. The next day we loaded up with 10 gallons of water (which later leaked a bit in the General II) and headed to the Usal Beach Campground located in the Sinkyone Wilderness State Park.

The only access to Usal Beach is via Mendocino County Route 431, a narrow one lane, dirt road with blind curves that can be steep in certain spots. After about 6 miles, we reached the campground. Then, our jaws dropped. The campground was packed with about 500 to 700 black-draped, tagged and studded kids sleeping off their activities from the night before. We drove around trying to find a campsite and eventually parked and went out and scouted for a place to camp. We spoke to several locals who were extremely irritated over the loud noise and partying that had happened the night before. We eventually found a campsite (Jim had scouted ahead and found it). We set up camp, made a short hike to the beach. That night we made burritos and listened to music drifting from the large group. Later we heard gunfire. The next morning, they had all cleared out, leaving a spotless number of campsites.

This park has mostly been abandoned, and I was skeptical about paying the camp fee since i was sure someone would rip it off. I later made a payment to the park via surface mail.

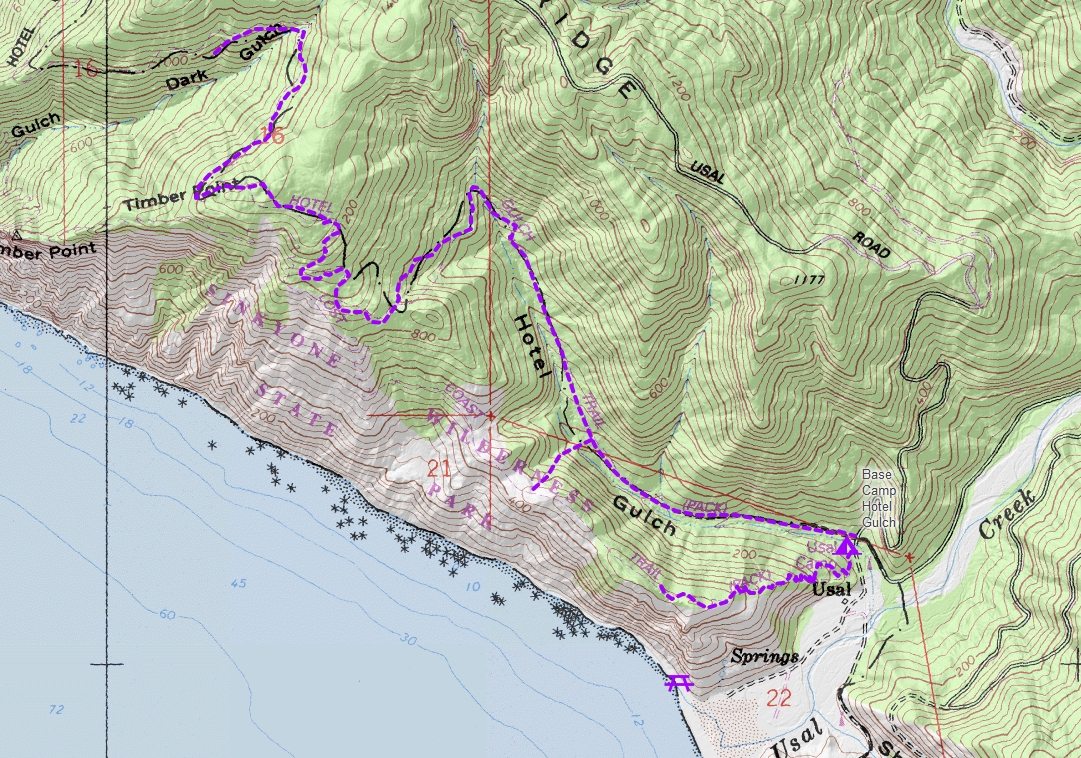

We had come here to do an hike to Anderson campsite along the Lost Coast trail (which parallels the coastline), but the lack of water and functional accurate maps made us hesitant to do this. We did do a short day hike along this trail and noticed it would be a bit of an up and down grunt, based on the comments other backpackers were making. We did see some great scenery, but were unable to identify a suitable spot to camp. The next day, we did a hike along the Hotel Gulch trail (essentially a road for quite a while) hoping to make a loop back to our campsite. After hiking a few miles, Jim discovered when going to a ridge to see the ocean that we were right next to the Lost Coast trail! Why anyone would hike up that trial when it could be reached by hiking up the simpler Hotel Gulch trail amazes me. After lunch and hiking for quite a while, we began to wonder if we had missed or not yet reached the return portion of our loop, so we reversed ourselves and headed back to our campsite. That night we dined on the beach and observed many dive-bombing pelicans and a seal which stared at us while we watched him.

The next day we packed up. Our campsite seemed to be in demand as several people parked at our site while we were packing to claim the site after we left. Sheesh. We drove back to Ft Bragg and checked into the Beachcomber Motel where Jim and Brian took a short dip in the Pacific Ocean. We also made a short trip to Glass Beach. From 1906 to 1967, everything (I mean everything) were pushed over the cliffs into the ocean. The end result was a number of smooth glass fragments creating a beach by way of wave action. That night we dined at Silvers on the Wharf. After leaving Ft Bragg for the drive home, we stopped at Jug Handle State Natural Reserve, a cool series of terraces having different stages of ecological succession.

On this trip we also stopped and examined a rocky inter-tidal basin, toured Mendocino, and had a tasty lunch at the Parish Cafe in Healdsburg.

After arriving back at Bob's house, Brian and Jim flew out of SFO the next day.

Maps? We don't need no stinkin' maps

The Sinkyone people lived in the area now known as Sinkyone Wilderness State Park for thousands of years before European contact. At the time the Europeans arrived, the Sinkyone population probably numbered as many as 4,000 individuals living in about seventy villages.

Starting with the California gold rush of the 1850s, the Sinkyones (and many other California natives) were decimated in less than twenty years. Their land was claimed by mining and timber companies and logged of most of its Redwood and Douglas Fir trees. By 1892, the year the Usal Lumber Company shut down for lack of timber, the demand for lumber had destroyed thousands of acres of virgin coast redwoods. The land continued to change hands frequently, with various attempts to revive logging operations. The Georgia-Pacific Plywood and Lumber Co. eventually purchased the land at the end of World War II.

In 1975, the state of California began acquiring local land to preserve as Sinkyone Wilderness State Park. In 1986, environmentalists sued to prevent Georgia-Pacific from clear-cutting a large parcel of land adjacent to the state’s holdings, including the old-growth redwoods in Sally Bell Grove. Before the case came to trial, Georgia-Pacific sold the property to the Trust for Public Land. In 1986, those acres were added to Sinkyone Wilderness State Park nearly doubling the park’s size.